MM: How did this project start?

EM: I had this idea: I’m going to make a baseball movie! It’ll be about a guy in an airplane who flies onto a baseball field and sings the national anthem. And then it’ll turn into a horror slasher film that takes place in the field.

And then I was like: I don’t have any money. How am I going to do this?

Much of this movie is about being confronted with the limitations of money, space, and time. I have to acclimate to the reality that I’ve been given.

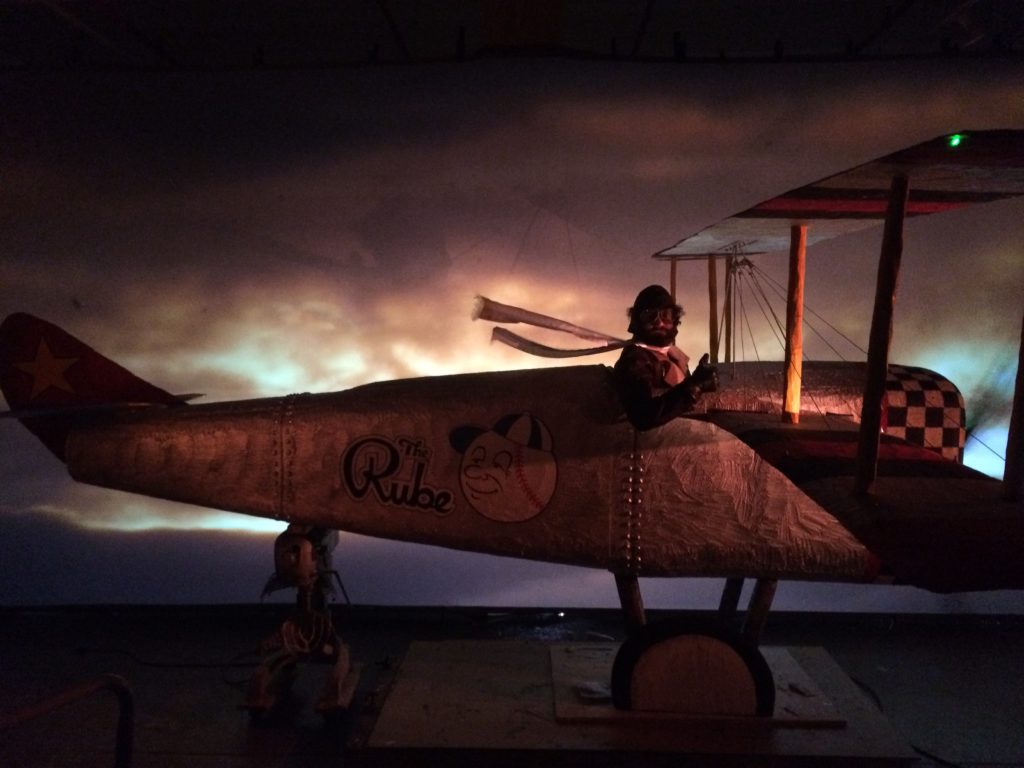

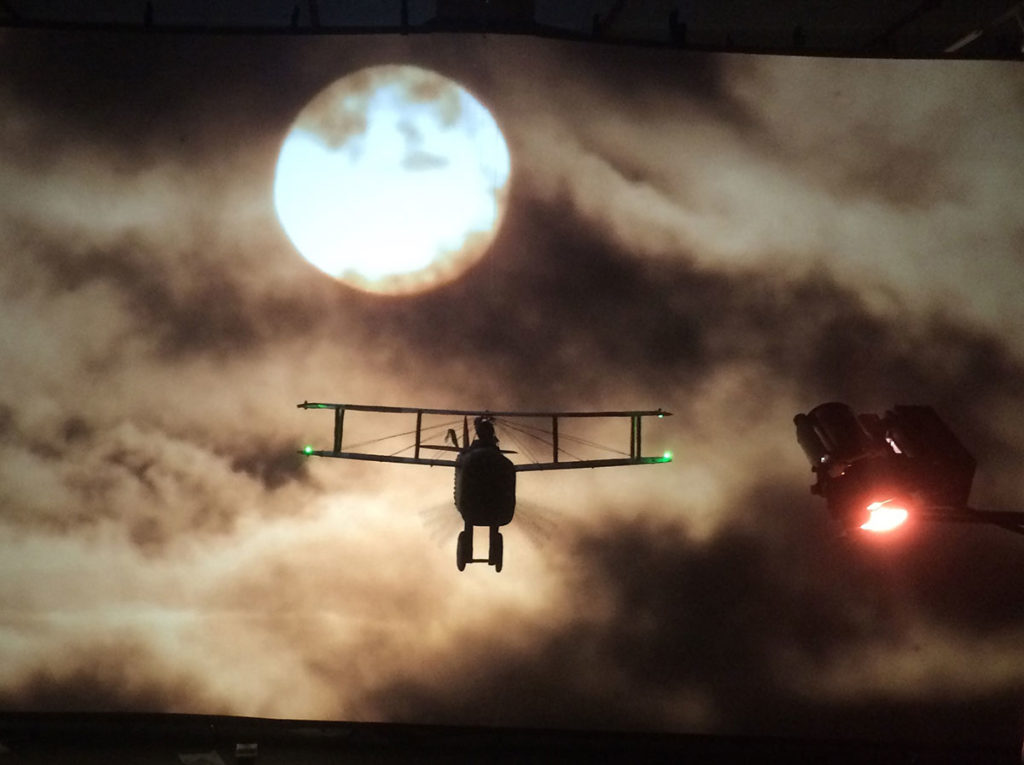

So my first thought was: I’ll build this airplane. I’ll have this guy in the airplane flying. He’ll look down through a telescope and he’ll see a baseball stadium. He’ll skydive into the baseball stadium, he’ll sing the national anthem. So I shot the thing and then I realized: he should see things when he’s flying. That would be more interesting than just the baseball stadium. And then I thought: I should build a bunch of miniatures for the landscapes he passes over. And so I built these canyons. Then, Oh! There should be a house in the canyon. And he should look and there should be a guy in the house. The guy in the house can have a little vignette. And then all of a sudden i realized: it doesn’t have to be about baseball. The guy can be listening to baseball game on the radio of the house. That’s how it’s about baseball.

Once I start making the movie I have room to figure out what it really is.

When I shot that airplane part, with the sunset, it felt really sweet. And then I started making the miniatures by hand, and that mood started to develop. And then I realized this shouldn’t be about a guy who goes and sings a song. It should be a meandering sweet narrative about the things that this guy sees below. Glimpses of people’s lives.

There’s this checking in with what I have and then a restructuring of the narrative to meet the needs of the mood and the feel I’ve started to establish.

I love stories but I don’t think I’m a great writer. I’m more interested in mood and creating a world. Because even in a great narrative movie you’re just left with a feeling. The ebb and flow of feelings and moods I find more interesting than creating some beginning, middle, and end.

MM: Did making the props help you figure that out? Or would you hire assistants if you could?

EM: I think about that all the time. Why am I making these? I just love building things. There’s something undeniably satisfying about it. And one informs the other.The miniatures, the canyons, the windmills, and the city scape: that took me maybe 3 months. Just showing up every day and tinkering.

Putting in the the physical labor, that creates a space to contemplate the narrative arc. Or at least what’s gonna happen next. I think if I was just sitting at my computer, thinking, “OK! What happens next?” rather than building these things, I would arrive at a very different place.

I really like having these distinctly different parts of the process.

In one, I think about: What do I want to build?

And then I think about what I’m building: how is that going to integrate itself into the narrative? And so there’s more writing. And then I shoot the thing. And then I edit it.

And then I see what I have. Cool. What happens now? I build the next thing.

Even with this car that I’m working on: I don’t know exactly what’s going happen inside the car. But I know that if I just start building it I’m going to have to figure it out.

MM: Did the impulse to build the plane come first?

EM: Totally. I love helicopter shots. Like the opening of The Shining. Any aerial shot. They’re just beautiful. I want to do an aerial shot! Wouldn’t it be cool to get a helicopter ride and attach a camera to the helicopter? But you can’t do that. It’s fucking expensive.

But I have access to this studio and this shop. It’s 23 feet long, so I can make a bi-plane that’s 23 feet.

And at the studio I sit and watch the sunset every day – we have an amazing view. So I can film clouds out this window and rear-screen project them behind this airplane. And now I have an airplane shot.

MM: Is this how you worked on Magic Ranch? Or was that a different process?

EM: Magic Ranch..I had no clue. But it was similar. I had access to a 20×20 foot space. I wanna make a western. How do I do it? Buy 1000 pounds of sand. Put it on the ground. Put a blue screen up and make a bunch of miniatures. It definitely came out of seeing what I had access to.

MM: It’s interesting, playing around with different moods, especially in terms of film history and tradition. How can I enter this established trope, and what does it have to offer? It seems like The Western is rich territory. How can we improvise on these established atmospheres that are part of the cannon of movie making?

EM: I saw Dunkirk yesterday. That has beautiful, cinematic airplane shots. And those Howard Hughes movies. All those airplane films.

MM: The big machine of possibilities.

EM: Yeah! It’s sexy and crazy and fun. That totally is part of it.

MM: But it’s just a starting point?

EM: It’s just a starting point.

MM: What’s the ideal viewing environment? Do you hope someone would see it in a theater? The way that I saw magic ranch was so specific, in that space you’d built.

EM: That movie really lent itself to that installation. Like Disney World. A part of me was thinking: Uh oh. Is this movie going to be accessible? I’ve got to ingratiate myself with these people. If you’re in the world and you’re drinking beer and there’s a guy playing guitar and you’re talking and happy and you see the control panels, and the whole world, you’d become more able and willing to engage in whatever was going to happen. Because magic ranch is kind of severe. Even if it was subconscious.

MM: I think that happened.

EM: And I had a lot of anxiety about showing it – so I was thought, “If I’m just really busy for three months before hand I can’t dwell on the feelings!”

MM: I think it’s interesting to make work while resisting a definition of the final product. When the outlet presents itself we’ll see how this project shapes into that. I mean, it sounds like you’re searching for a way for this process to be the most fun it can be.

EM: Well it’s nice to let it be an organic process. And I’m not totally in my head. I talk to Keegan [Monaghan] about so much of this stuff. I have to have someone to show the thing to, bounce ideas off of. That’s an interesting part of the process too. It is very collaborative at the end of the day.

MM: Did you write the parts for specific people or did you find actors after the fact?

EM: The pilot is Jonathan Campolo, who is a friend. He’s really charismatic. He just moves and behaves in a really great way. And the guy in the cabin is J. Dixon Byrne, who I saw in James N. Kienitz Wilkins’ movie at the Whitney, Mediums. That movie’s really great. Emerson Greenesmith is in it. But this actor was so interesting. He has these big blue eyes…the way he moves…I thought he’d be interesting. So I met with him, talked to him about the scene, and showed him what I had so far. He really got it. It was the first time I had worked with someone I didn’t know.

I think I can get in trouble if I only cast friends. It’s just not as interesting.

MM: Miniatures and models in an art context are sort of obscured by this dense theory…I feel like if I was talking to somebody about making miniature sculptures it would be a very different conversation. “Escapism” always worms its way in – building an idealized world, something like that.

EM: A utopia.

MM: But I wouldn’t call Magic Ranch a Utopia, exactly…

EM: What?! You missed it!

MM: But I’m curious…you keep using the word “sweet” to talk about this movie. Is it because you’re building these little worlds? Maybe it lends itself that feeling, more so than something as intense as Magic Ranch.

EM: Well what’s funny is that I think there’s even a sweetness in Magic Ranch. Obviously it’s different – it’s abject, it’s gross, it’s really stupid and sophomoric.

There’s this movie that I love and think about a lot. It’s called Bad Taste. It’s Peter Jackson first movie. He made in New Zealand when he was 22 or 23. He shot it on the weekends with his friends. It’s a slapstick horror about aliens that come to New Zealand and try to eat humans. They go after humans because they have an intergalactic fast food restaurant that sells human hamburgers or something. But he made everything in his garage. All the special effects, all the alien masks, everything. He made the molds in his mom’s oven, that kind of thing.

It’s really gross and stupid but you can feel how inspired it is. It’s so ambitious. There are these crazy shots – like a house levitates and flies away! They had no money! How’d they figure this out?

And like while the content isn’t sweet, you can just see the care that went into it. They cared for that thing so much! It’s fucked up and imperfect but so great, so wonderful. So i think that’s what I mean when I say sweetness.

MM: The sweetness of this project is bound up with a kind of nostalgic atmosphere, but it doesn’t ever fall into escapism. It feels generative, rather than reactionary.

EM: I think escapism is probably inherent in everything that’s made!

But that’s not the point of the movie. I do think that’s why i make everything myself. It’s something to do with my day! I know what I’m gonna make. I don’t have to think about it. I have to make 50 of these. There’s something almost meditative, something soothing, about being able to just show up and know that i have to make 100 buildings. I definitely think there’s escapism in a productive kind of way.

MM: By “escapism” I was thinking more, like…hanging a Thomas Kinkaid landscape or weird painting of a cottage in your house.

EM: Sorry! I was talking about my feelings!

Yes…there’s not a literal idea of trying to get away. That’s not at the forefront of my mind. But it is nice to make something that feels sweet and dreamy and nostalgic and sentimental. I hope it works! I guess it is a bit of a reaction to reality.

MM: It’s an interesting aspect of the work that I’m trying to figure out how to talk about – without simplifying a complex process. Or adding a specific back story.

EM: What do you mean by back story?

MM: That’s probably the wrong word. You know, like: “I’m creating this world because I hate Donald Trump.” Which I don’t think you’re doing. But atmosphere and tone is really hard to talk about. It’s kind of taboo. Like “taste”. And I think that the way you’re playing with it is very exciting. Usually, when people make work that’s nostalgic it feels cheap. Like a shortcut to emotional authenticity.

EM: I think about that a lot, Maren. I’ve been hesitant to talk about it right now because someone might watch this and be like: this is the most hoaky hallmark shit! I don’t know. I hope not.

So the movie takes place at the golden hour. The sun is setting. It’s really moody. The guy smokes a cigarette sitting on the airplane. It doesn’t follow the rules of reality. The lighting doesn’t make sense. My hope is that it can be sentimental or sweet in a way you wouldn’t be able to get away with if it were to take place in reality.

I spend so much time with the thing. I can spend a year on it and watch it thousands of times, and at the end of the day someone is going watch it for 15 minutes. That’s the experience. Ad I’ll never know what that feels like. It’s impossible. Hopefully it does something that’s interesting.

MM: What are some movies you love?

EM: I was just watching that movie Brazil the other day – and that movie is just so cool.

There’s one movie I think about all the time. I actually wrote the filmmaker who made it, her name is Mary Hestand, and we have a correspondence going – it’s so cool – it’s called He Was Once. It’s a short film from the 1980’s that Todd Haynes co-produced.

It’s live action but made to feel like stop motion. Remember David and Goliath?

They shot He Was Once at a higher frame rate and had the actors move slow, or something. But everyone looks like they’re claymation. It’s surreal. And the costumes are these weird ears and weird clothes. The whole world is handmade.

The whole world is fully realized in every sense. Every time I think of it or watch it – the feeling of that thing is so singular. I’ve never seen anything that feels like that. And to me that’s the most interesting art. It transcends. What was that? It felt so weird. And that’s the thing that lingers.

And Ernie Kovacs: he was a comedian in the fifties who was given a variety show on ABC. They were just experimental television sketches. Really trippy. He was doing all these weird in-camera effects, playing with video, playing with camera angles, music. I bought a box set of all those things a while back. They’re not even that funny. He’s clearly working within limited space and technology. But figuring out a way to do things that’s so interesting.

There’s one he did that’s all silent. It’s just this guy walking around – he opens up Gone with The Wind and it blows him backwards. Stuff like that. Slapstick. But it’s 25 minutes! It’s too long, and it’s not funny really. His stomach grumbles. He drinks water and it goes [slosh slosh] in his stomach.

MM: Like the really good three stooges episodes.

EM: Yeah but even more abstract. It becomes this artful, weird thing.

MM: It’s funny that you said early on, really emphatically, that this film is not experimental.

EM: I think I was being a little extreme. I could see how there are components of this film that could be thought of as experimental, but my hope would be that this movie is something that anyone could sit down and watch.

MM: Would you ever want to make a piece that’s the environment, the props, without the film?

EM: Totally. I mean, i would also love to make a movie that’s NOT all super handmade.

I think the reason film feels so stimulating is that it’s everything. It’s writing, it’s acting, it’s sound, it’s music. I can make paintings and sculptures and put them in there if i want. They’re props – but I dunno. Is it a sculpture?