Maren Miller talks to Bela Shayevich about her big drawings in Serial Killer Land

Have you always made both stand-alone drawings as well as zines and comics?

My first drawings were angsty doodles. These incorporated both text and image – I used whatever I could to convey the violence of my boredom. For instance, in high school, I drew all these pictures of Hitler, usually naked and on all fours, saying stuff. I also did a comic strip called “Elephant and Mouse” in which one or both of them would always kill themselves, often by crucifixion. The first time I made a book, which is to say, the time I made 27 copies of my unbound collection of poetry, “The Magnificent Eros,” about half of it was illustrations for the poems. I would say that I have always done illustration, and my overall arc so far has been moving away from text, but replacing it with other narrative devices.

The book I am putting out in conjunction with this show, Doing It Softly, XO: Contract Killer, is a sequence of drawings with some story, but barely any text. It’s not quite a comic, though it is easiest to call it one. It is more like an animation than anything else.

Are these drawings a move away from the narrative (the linear book) or more of an exploration of what narrative can be (things happening simultaneously on the same picture plane)?

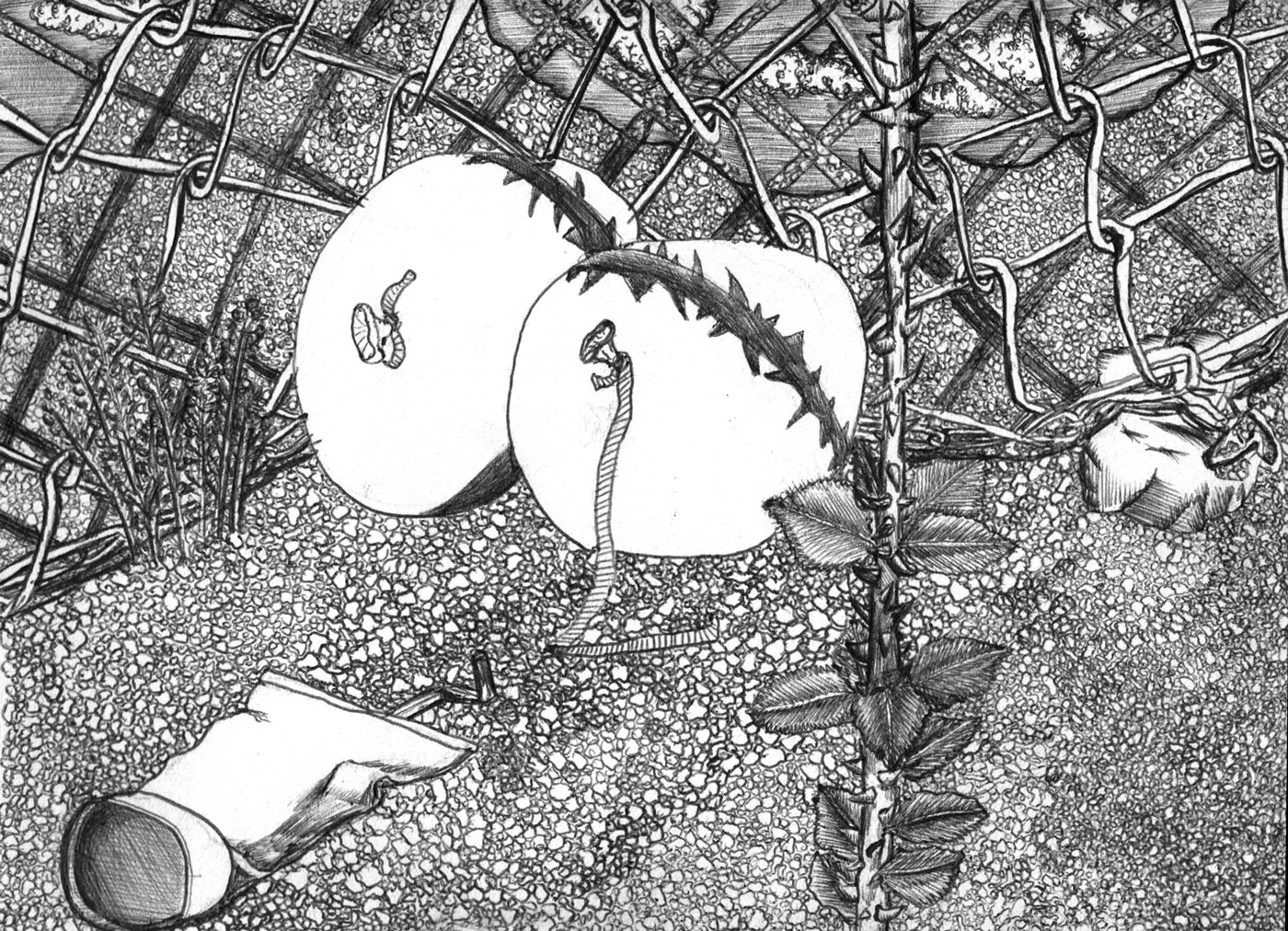

I am interested in how many ideas I can cram into a single drawing, which will include the narratives that inspire it as well as all relevant symbolism, political messages, visual games, and so on. While trying to fit everything on the same page, I make lots of different drawings that can be seen at different scales depending on how close you stand to the picture. Narrative itself, in terms of telling a specific story, is not as important to me as figuring out how to package all of these elements and ideas into a chaotic whole.

Are these the first large-scale works you’ve made?

I began drawing on big pieces of paper in order to move out of making doodles and into making something more substantial by forcing myself to have to reckon with a lot more space and all the time it’d take to fill it. The first big drawing I made, “Everybody has their own rape van,” didn’t have a planned composition, and I didn’t use pencil or anything – it was just ballpoint pen on a big piece of paper taped directly to my wall. Whatever I thought of drawing on it that day. It ended up looking like something by Breughel, but with lions attempting to sexually assault women on a basketball court. The other two drawings continued this approach of filling a large scene with a bunch of little characters. So they were big, but the scale in them was still small. The bathroom drawing in this show, “A mysterious watcher in blue,” was the first drawing I’ve made where the figures actually correspond to the size of the paper in a way that is more of a healthy departure from the sketchbook. But then I started drawing big spaces, so the figures are once again small. I’m working on the scale thing.

I’m really interested in your use of pattern. Its treatment creates this nauseating effect that evokes not only motion but also a kind of moral dimension: that the meticulous rendering serves a goal that is not realism. The repetitive pattern-fields elevate the process behind these drawings to the same level of importance as the subject matter and method of depiction. You can feel the hours that went into those sections. Like the scars on the flagellant’s back.

Before I apprehend a space as an ‘artefact of an oppressive society’, I experience it as scary and upsetting. I feel anxious at the airport, dirty in a public restroom, depressed but free in a parking lot. The fear precedes any intellectual or moral verdict. In terms of how this plays out in my work, I see drawing the patterns that form these places as a game where I am given a boring task and test whether or not I can perform it. Invariably, I cannot. In the same way, I can’t remain calm around endless expanses of fake-sterile tiled surfaces. Tiles so easily morph into cages.

A lot of the time, I curse myself for choosing to draw what I am drawing, and hate the process. However, I do believe that depicting these spaces is worth the boredom and self-flagellation. When I was drawing the airport, I started making the joke that I’m the new M.C. Escher. Patterns, tiles and rugs and so on, are everywhere – they’re what fill these spaces. They’re supposed to be the uniting elements that make surfaces look coherent and regular, consistent with other spaces of the same kind. Maybe even soothing. On closer examination, they are inanely designed, arbitrarily combined with other patterns, sloppily applied, (maddening,) and, taking into account topography and lighting, they look different at every inch. Their regularity is only a generalization – no surface or pattern is actually regular. If I actually had to draw the pavement of a parking lot in the way that it is idealized to be – as something that is evenly applied across an entire giant surface – I would jump out of my skin. And I’d have to, because I don’t think I have the technical skill or the patience it takes to acquire it to be a real M.C.E.

Luckily, the world is just as bored with consistency as I am. It might look zany and nauseating in my drawings, but if you actually observe the pavement, you will see that it is very patchy and diverse in real life. The motion and disorientation in my rendering of these patterns illustrates the contradiction between the way the world wants you to see it – as normal and controlled – and what is actually in the world, chaos. But the way I bring things to light might simply come from my physical inability to see or draw the world the way it wants to be seen.

This work seems so much a function of memory. Do you ever draw from life? Either directly in these spaces or otherwise?

For these drawings, I’d jot down details on location or make sketches, and visit places over and over. I obsessively observed. For instance, while doing the bathroom, I couldn’t stop noting and taking photos of tile patterns in public restrooms; during the parking lot, my eyes were always on the pavement, wherever I went. Loitering turned into ‘soaking up space.’ I didn’t draw in any of them directly – the drawings are too big! – but maybe I should for my next series, which is about the nursing home where my grandma is dying.

I think I may be inordinately interested in your subject matter because I just finished interviewing another artist who has been largely painting scenes of love and leisure. So I ask myself (however simplistic it may sound) why do we represent this and not that, and vice versa?

I also draw love and leisure, but those drawings are about loneliness and depression. That’s what Doing It Softly, XO: Contract Killer is about. Not easy to draw about happy love if you got none. But pretty easy to experience the pain of lacking love when it is represented as the only path to a woman’s fulfilment. The big colored pencil drawings are about love and leisure, too – they’re about extremely lonely experiences I had when not at work. Experiences that made me feel like I was in hell, the pain of which was amplified by my loneliness and depression. But what I found was that the pain I’m experiencing and describing is much bigger than me – it’s universal and political.

I feel that the grating surface of American realia is insufficiently dramatized as the instrument of personal torture for everyone who experiences it. There is so much ugliness, but we take it for granted because it is everywhere and we all work very hard for the opportunity to partake in it. We don’t want to talk about it, it’s too big and unmovable. The way people live in New York City: full of poison, overpriced food; fumes; tiny, humiliatingly expensive living spaces. People are too embarrassed to complain about the garbage out their windows, the garbage their homes are built of, being treated like garbage at their jobs, and being fed garbage day in day out because it’s supposed to be our own fault if we can’t afford to live near trees or buy organic. Most people feel like there’s nothing they can do but ‘think positive’ and try their hardest to get rich. To me, this feels like an emergency.

Images of love and leisure have been completely commodified by advertising. Perhaps liberating figurative representations of happiness from advertising would be a noble and very difficult pursuit, but I want to get a grasp on the contours of the darkness that advertising and media seek to white out before trying to rescue the images that are used to oppress everyone.

Do you think you’ll continue making large scale drawings?

I really want to work faster so I can process ideas and move through phases at a better clip. My next project will definitely have smaller drawings, except… there’s going to be 13 of them.